- An important reforestation project is forging ahead in Haiti, despite the nation’s economic and political upheavals.

- Reforesting 50 hectares (124 acres) with native plants this year in Grand Bois National Park, the NGO Haiti National Trust (HNT) is working closely with local communities to ensure the restoration project’s long-term survival.

- On an island buffeted by governance woes, severe deforestation and climate change, reforestation can save lives by mitigating the impacts of extreme rain events, droughts and hurricanes, and even reduce the risk of landslides caused by earthquakes.

- If ongoing funding can be secured, the group hopes to continue replanting efforts into the future with larger restoration goals.

Haiti is in profound crisis again. The Caribbean nation, occupying the western third of the island of Hispaniola is suffering from an escalating bout of political instability, following the assassination of Prime Minister Jovenel Moïse in 2021; just last month, another prominent politician, Eric Jean Baptiste, was shot dead.

Add to that an expanding cholera outbreak and violent gangs blockading so many streets that the current government of Ariel Henry, the acting president and PM, is pleading for international intervention to help reopen vital supply routes to the impoverished populace. All this in a nation facing down formidable environmental crises, including extreme deforestation, erosion and freshwater issues.

But amid these difficulties, Haitians remain resilient, with NGOs and individuals joining together to make a difference.

A tropical reforestation project launched in 2019 offers a prime example: It is not only on pace to meet its 50,000 plantings goal, but hopefully will hit 60,000 plantings by the end of the year, according to the Haiti National Trust (HNT) and its international partner Re:wild, funded in part by celebrity Leonardo DiCaprio.

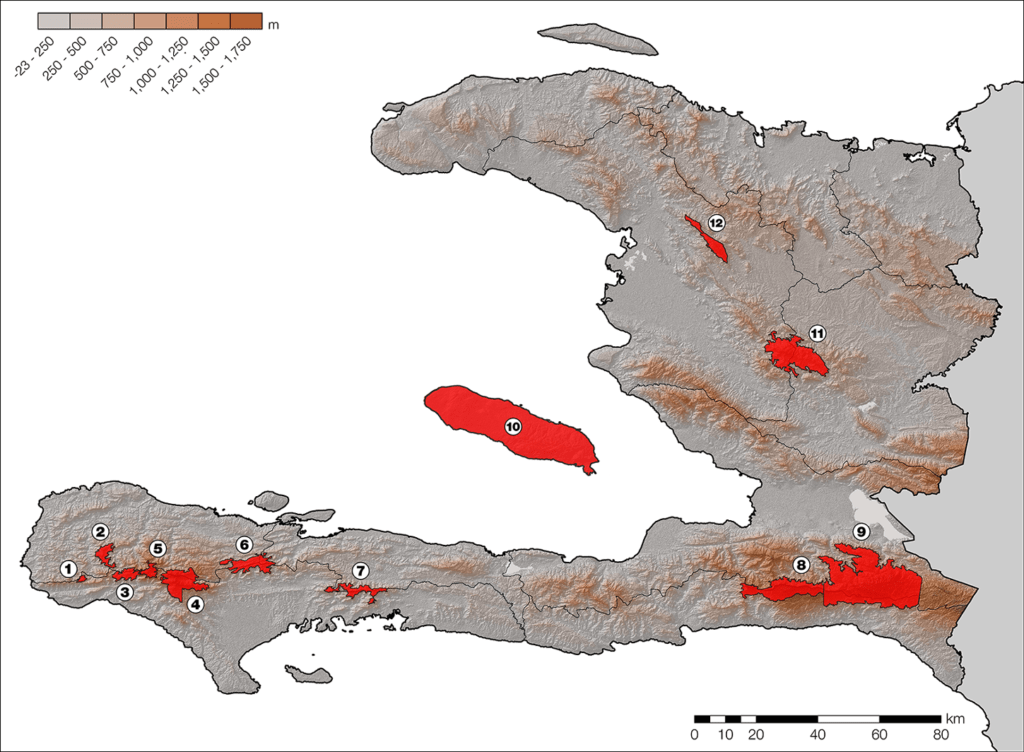

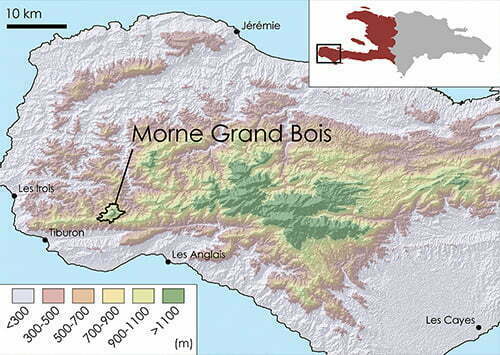

Seedling by seedling, the NGO coalition in partnership with local communities is restoring 50 hectares (124 acres) of one of Haiti’s last surviving biodiversity hotspots: the Massif de Hotte, a mountain range that runs from 900 to 1,250 meters (2,950-4,100 feet) in the country’s recently protected Grand Bois National Park near the western tip of the Tiburon Peninsula.

“Grand Bois National Park is unique in that it has among the last remaining primary rainforests occurring at mid-elevation in Haiti … with a significant number of threatened and endangered species,” said HNT conservation director Joel Timyan, noting that the site is a Key Biodiversity Area and home to a number of populations — possibly the very last refuge of their species.

An island nation besieged

Haiti’s chronic sociopolitical and environmental misfortunes can be traced to 1492, the year Christopher Columbus “discovered” it, favorably describing the already heavily populated island of Hispaniola’s environment as “most fertile” with its “very lofty and beautiful mountains, great farms, groves and fields,” along with forests “filled with trees of 1,000 kinds so tall they seemed to touch the sky.” The Spanish rapidly committed genocide against the island’s native people, with several hundred thousand to a million Indigenous Taino killed by enslavement, massacre and disease, until a mere 32,000 survived by 1514. Over the ensuing centuries, colonizers pillaged the island environment via a plantation export economy.

Currently the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, Haiti has lost almost the entirety of its ecosystems.

Less than 1% of the nation’s primary forest is thought to remain, with less than one-third of the country currently cloaked in secondary forest, according to Global Forest Watch. Haiti’s tree loss is tied today to its poverty: much of its tropical forest has been cut to make charcoal, for slash-and-burn agriculture, and for building materials. Add to this, worsening climate change and a beleaguered government unable to fully respond to myriad emergencies.

But given the nation’s daunting challenges, Haiti’s conservationists continue striving to find innovative ways to ensure the Massif de Hotte project’s trees live to maturity.

An ambitious project in its infancy

Grand Bois National Park is a very recent creation, established in 2015 by then-president Michel Martelly. The project to reforest a portion of this ecologically important landscape began in 2019, when HNT started collecting seedlings of endemic plants, including the critically endangered Ekman’s magnolia (Magnolia ekmanii). The seedlings were raised in nurseries, with plantings initiated this year across 50 hectares of Grand Bois.

From the start, the project used an innovative public-private land stewardship approach. In 2019, HNT, Re:wild (formerly Global Wildlife Conservation) and the Rainforest Trust purchased about 500 hectares (1,235 acres) of forest adjacent to, and overlapping with, Grand Bois National Park, creating the country’s first private reserve. Purchasing land inside the park, which is legally permitted in Haiti, allowed the NGO coalition to work there with less red tape.

Progress has been rapid, despite recent road closures and widespread unrest, which make reforestation “much more challenging,” said HNT executive director Anne-Isabelle Bonifassi. “Our planting pace has lowered, but we kept working and we are still on target.”

Bonifassi adds that they plan to reforest even more next year, and to keep doing so as long as funding continues.

Grand Bois National Park is one of the most biodiverse ecosystems left in Haiti. Just this year, researchers rediscovered a magnolia species in the park that had not been seen by scientists for 97 years: the northern Haiti magnolia (Magnolia emarginata). This lost-then-found magnolia is one of five magnolias, including Ekman’s, only found on Hispaniola.

The small park is also a frog paradise: to date, scientists have recorded 24 species of frog there. Three are new to science and currently undescribed. One is the critically endangered Tiburon stream frog (Eleutherodactylus semipalmatus), thought extinct for decades.

It’s “a rare aquatic species in an otherwise terrestrial group of frogs,” according to S. Blair Hedges, an HNT co-founder and director of the Center for Biodiversity at Philadelphia’s Temple University. Blair Hedges has spent years surveying Haiti’s last wild areas.

The scientist notes that more than 90% of Haiti’s amphibians are threatened with extinction — the highest percentage of any nation in the world. In Grand Bois, 22 of the 24 frog species are threatened, with 16 of those critically endangered on the IUCN Red List.

Jenny Daltry, the Caribbean alliance director at Re:wild, says the park has only been “partially surveyed.” That means many more discoveries could await.

Grand Bois, with one of Haiti’s last standing primary forests, also offers many ecosystem services making life better for Haitians. The trees buffer local communities from hurricanes, erosion and landslides brought on by climate change-intensified storms and by the island nation’s frequent earthquakes.

“In short, having trees in the right places saves lives,” said Daltry.

The park’s trees also safeguard freshwater sources, including springs, rivers and aquifers, according to Timyan. That’s increasingly important due to more frequent droughts. “If these areas are deforested, then the frequency and severity of floods will increase, and desertification mechanisms will result in less base flow and a decrease in water quality,” he explained.

Planting more native vegetation will also enhance the forest’s ability to “absorb catastrophic disturbances,” Timyan said, ranging from torrential floods to wildfires.

Emphasis on local community involvement

Reforestation projects face numerous challenges worldwide, including insufficient funding, water access, and the capacity to care for trees many years after they’ve been planted. Given Haiti’s many extreme trials, a major difficulty is assuring the plants aren’t cut illegally to provide charcoal for cooking or construction materials.

HNT has turned to its community partnerships as a way of safeguarding both the park and the reforestation project.

“Because of the current [economic] situation, it’s very challenging to find local support, as most people, understandably, have other priorities,” said Bonifassi. But, she stressed, HNT is finding ways to work with local villages to ensure seedlings take root and grow tall.

One winning strategy: HNT hired dozens of locals to do much of the work, including planting, caring for seedlings, and removing invasive species. In a country where the unemployment rate last year was more than 15% — and continues rising — employment matters. Bonifassi notes that HNT also partners with villages to find revenue-generating alternatives to charcoal burning or agriculture inside the park.

“It’s important for Haiti National Trust to keep working with [local people], and discuss sustainable agricultural practices and other ways to generate food and an income to ensure they are not too impacted … by a crisis like this [current] one,” she said.

One such alternative livelihood is beekeeping. A number of local farmers already had beehives, but lost them to Hurricane Matthew in 2016. So last year, HNT joined with 25 small-scale farmers to rebuild hives. The NGO also meets with local villages to learn what economic activities would be most helpful to them.

“What’s important is that these ideas have to come from [the people,] based on what they can do, and what they want to do … In no way do we want to impose anything,” said Bonifassi.

Good ideas arising from these community sessions include the growing of coffee, cashews, avocado and citrus using agroforestry practices. Another idea is to harvest invasive plant species and build furniture from them. Unfortunately, these ideas currently wait on funding to be implemented.

“The future of most high priority biodiversity sites in Haiti depends on developing genuine partnerships with local communities, and enabling them to become both the stewards and beneficiaries of conservation,” explained Daltry.

Big hurdles ahead

Even as HNT builds community relationships, forest protections remain at risk, with the Grand Bois National Park only employing one full-time ranger, said Bonifassi. “We are looking for more funds to hire a team of six to nine rangers patrolling the park. This team is vital to the [long-term] success of our reforestation efforts.”

Escalating climate change poses another future threat — as it does the world over. “All Caribbean islands are already feeling the impacts of climate change, including record-breaking hurricanes and other extreme weather events,” said Daltry. “This is putting Haiti’s people in real danger, exacerbated by the island’s severe deforestation problem.”

Climate change could lead to extinctions in Grand Bois. As island montane forests feel the heat, species blocked by surrounding oceans can’t migrate poleward. So they must migrate upslope to maintain optimal temperature. But scientists fear some species will vanish once they run out of mountain to climb.

Still, there are ways to buffer against future loss. “By planting a well-considered mixture of native species that are perfectly adapted to this environment, the new forest will have a high level of resiliency — undoubtedly far greater than planting a monoculture or importing species that are not native to Haiti,” said Daltry. “Climate change is bound to test the new forest, of course, and not all species may survive to the next century. As long as most other threats are minimized, however, more trees will cover and stabilize the slopes and the forest will continue regenerating.”

Of course, Haiti’s and the world’s future depends on how quickly humanity can kick its fossil fuels habit. In that regard, “HNT is actively seeking investments to finance this transition from an economy based on resource extraction and mining toward one that is based on a wiser use of renewable resources,” said Bonifassi.

Still, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by Haiti’s many crises, and by whatever lies ahead. But that still isn’t stopping conservation groups and local people from striving further to protect the nation’s remaining ecosystems.

“The past months have been very difficult for Haiti and its people, and it feels like we only hear about Haiti when bad or negative things happen, but Haiti is not just that,” Bonifassi said.

“Haiti is a rich and beautiful land with amazing biodiversity that we need to protect; Biodiversity ignores political conflicts,” she declared. “This is our heritage and despite the many challenges that this civil unrest brings, our teams are in the field, working with local communities on rewilding our country for future generations.